Convex functions near zero, and a surprise proof of $e^x - 1 >x$

$\newcommand{\e}{\varepsilon}$

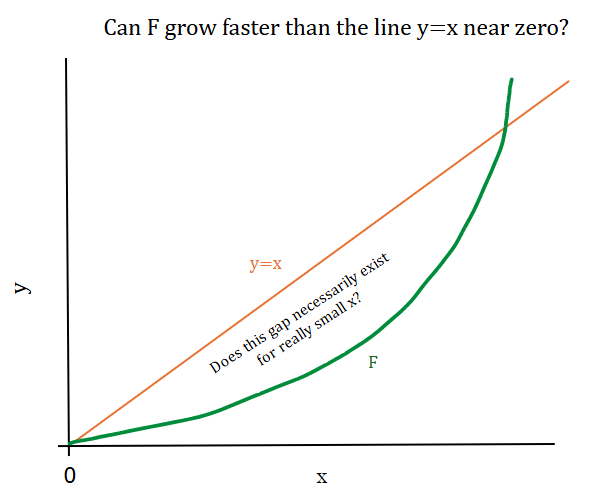

Question: if we have a function that is $0$ at $0$, and increases from there while being “curled upward”, does a line initially (maybe for really small inputs) grow faster than it?

Here’s a more precise version of that question. Consider a function $F : [0,\infty) \to [0,\infty)$ with the following conditions:

\[F(0) = 0; \quad \exists \e > 0 : \forall x \in (0,\e) \;F'(x) > 0 \text{ and } F^{\prime\prime}(x) > 0 \tag{1}.\]Conjecture: if $F$ satisfies $(1)$, must we have $F(x) < x$ for $x$ in some neighborhood of zero?

I’ll give the context for this at the end, but for now I’ll just consider it on its own. The first function I used to check this conjecture is the trusty convex polynomial $x^n$ for $n$ big. The conjecture happens to be true for such functions. $x^n$ can’t somehow curl up fast enough to be above $x$ for small inputs.

Despite this, it turns out that it’s pretty easy to find examples of functions that satisfy $(1)$ yet the conjecture is false for them. $x^n$ doesn’t work because its slope near $0$ approaches $0$ (the derivative is $nx^{n-1} \to 0$). What if our convex function had a derivative of at least $1$ near zero?

One example: $H(x) = e^x-1$. This satisfies $(1)$: $H(0) = 0$, $H’(x) = e^x > 0$, and $H^{\prime\prime}(x) = e^x > 0$. We also have $H’(x) > 1$ near zero, so the slope of the function is greater than $1$ no matter how close to zero we get. It is a standard mathematical fact that $e^x - 1 > x$ for all $x > 0$, so this refutes the conjecture.

$H$ is not unique, and we can produce many more such functions in the following way. Note that $x = \int_0^x 1 \,\text dt$, and so the slope is $1$ by the fundamental theorem of calculus (a rather convoluted way to arrive at that fact). To get a function with a faster slope near $0$, we just need to integrate something that’s bigger than $1$ near zero, as if $f > g \geq 0$ on $(0,\e)$ then $\int_0^\e f > \int_0^\e g$ (this is the monotonicity of integration).

Well, one such function is the constant $2$. Does that work? $F(x) = \int_0^x 2 \,\text dt = 2x$ satisfies $(1)$, if we relax to allow $F’$ and $F^{\prime\prime}$ to be zero instead of positive. This gives us the rather-expected result that the line $y = 2x$ is always above the line $y = x$ for positive inputs. So that’s nearly an example, but it’d be nice to get some with positive curvature.

Let $f$ be the integrand, so $F(x) = \int_0^x f(t)\,\text dt$. We could try a function like $f(x) = ax^p + 1$ for $a,p>0$. Then $f > 1$ near zero, and $F(x) = \frac{a}{p+1}x^{p+1} + x > x$ near zero, with polynomial growth away from the line $y=x$. So that works. We can get even faster growth by adding up more polynomials, and in the limit we can arrive at $f(x) = \sum_{n=0}^\infty \frac{x^n}{n!} = e^x$. $f(x) > 1$ for all $x > 0$, so

\[\int_0^x f(t)\,\text dt = e^x - 1 > \int_0^x 1 \,\text dt = x.\]This gives us a proof of the earlier fact that $e^x - 1 > x$ for $x > 0$! I haven’t seen this particular proof before, hence my surprise.

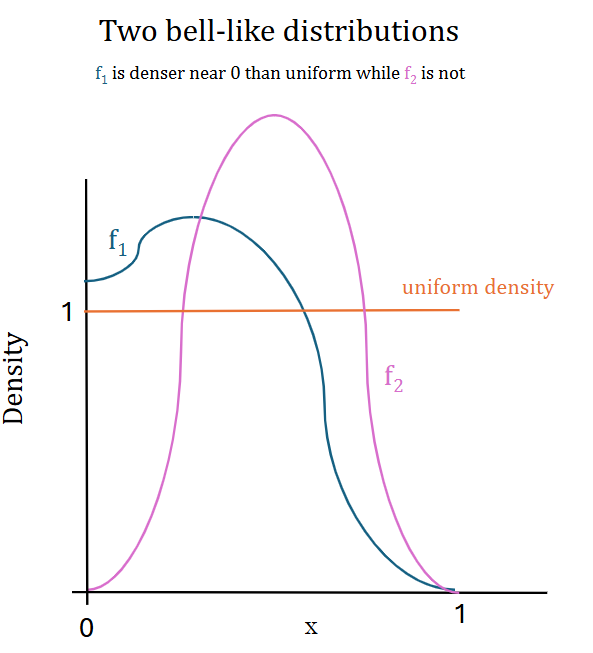

The original context of this was a question about cumulative distribution functions. Consider random variables (RVs) $X$ and $Y$ restricted to $[0,1]$, where $X$ has a bell-like shape (so it is smooth, unimodal, increases up to a single global max with an inflection point along the way, and then decreases after that max with another inflection point) and $Y \sim \text{Unif}(0,1)$. $F$ will denote the CDF of $X$, and $G(x) = x$ on $[0,1]$ is the CDF of $Y$. We want to know if $X$, being convex below the smaller inflection point, is necessarily less concentrated near zero than the uniform $Y$.

The above comments give us our answer: if the density of $X$ gets small, vanishing like a Gaussian does on $\mathbb R$, then we do indeed have $X$ less dense than uniform in a neighborhood of zero. But we can have a bell-like curve without this happening, as shown in the figure below. So the density having a bell-like shape, and the CDF having a corresponding sigmoid shape, are not enough to determine if the RV in question is more or less concentrated near zero than a uniform RV.